Dangerous States of Mind

What to do when workers are frustrated, fatigued, complacent or hurried

This article by Larry Wilson is reprinted with permission from the May 2001 Issue of Industrial Safety & Hygiene Magazine.

While most safety and health pros contend that rushing, frustration, fatigue, and complacency are major contributors to safety problems, convincing your boss to do something about it can be difficult.

What follows is a fictional dialogue between a safety and health pro and his boss. Hopefully, it will serve as a springboard for broaching the subject in your own plant.

Note: from a humour standpoint, it helps to picture the pointy-haired manager from Dilbert, or an HR manager who doesn’t know much about safety or an operations manager who thinks safety is your responsibility—not theirs. Obviously from a reality standpoint, it helps not to have a boss like that. However, no matter what kind of boss you have—if you want to keep improving, eventually you’ll have to discuss these states or human factors.

You walk in to your boss’s office and say, “Guess what? I just figured out that rushing contributes to injuries.”

He looks at you with that pained, paternal expression you’ve come to despise and says, “Did you figure that out all by yourself or did you get help?”

You ignore the temptation to demonstrate the concept of line-of-fire and press on. “Frustration causes injuries too,” you say. Again you get the look, but this time it’s more like a judge on one of the TV police shows, you know, that “I’ll let you keep going but this better be good” type of look. So you say, “Fatigue causes injuries as well.”

“No kidding Sherlock,” he says.

“And so does complacency,” you add quickly.

“What exactly is your point?” he says, starting to get a bit riled.

“My point is, you can’t tell me of a time you’ve been hurt when you weren’t rushing, you weren’t tired, you weren’t frustrated or you hadn’t become so complacent with the hazards that you just weren’t thinking about the risk of getting hurt at that moment.” You pause, then add “…except for contact sports.”

He stops and thinks, and then writes the four states down on a piece of paper. After about four or five seconds he looks up at you and says, “You’re right—I can’t.”

“Do you think you—or me, for that matter—do you think we’re all that much different than everybody else in the plant?”

The look you’re getting now has improved tremendously. “Not likely,” he says, … “But so what? I mean it’s not as though we can eliminate rushing, frustration, fatigue or complacency. They’re part of life.”

“We can’t eliminate them,” you say, “but we can minimize their effects.”

“How?”, he asks.

“Well, there are things we can do from a company perspective and there are techniques we can all use, on a personal basis, to minimize the impact these states or human factors have on us.”

“Give me a few examples,” he says.

“Well from the company perspective, we can train the folks working shifts on how to cope with the shift work better so they get more quality sleep. We could even look at different types of shift rotations. Moving away from piecework incentives could reduce rushing. More communication should reduce frustration. And behavior based safety observations will improve awareness and help us fight complacency.”

“Oh,” he says, “I see what you mean in terms of things the company can do, but what about the stuff on a personal basis? How does that work?”

“Well (here goes, you say to yourself), first of all the state contributes to the injury but the state alone isn’t enough to get you hurt. There also has to be a hazard or some hazardous energy, and this hazardous energy has to come in contact with you or you have to come in contact with it.” He doesn’t look like he’s getting it so you say, “either you hit something or it hits you. Now if it hits you, you could think of yourself as being in the path of the hazardous energy or the line-of-fire. And, in order for you to move into a hazard, it’s very unlikely you’d do that if you were looking at it or thinking about it, unless somehow you lost your balance, traction or grip and moved into it inadvertently. So usually there are at least three factors: a state like rushing which increases the likelihood of an errorlike eyes not on task which increases the likelihood of contacting a hazard or having a hazard contact you.”

Critical errors

At least one of these four possible errors is involved in many safety incidents.

- Eyes not on task

- Mind not on task

- Being in the line-of-fire for the hazard

- Losing balance and inadvertently falling into the path of the hazard.

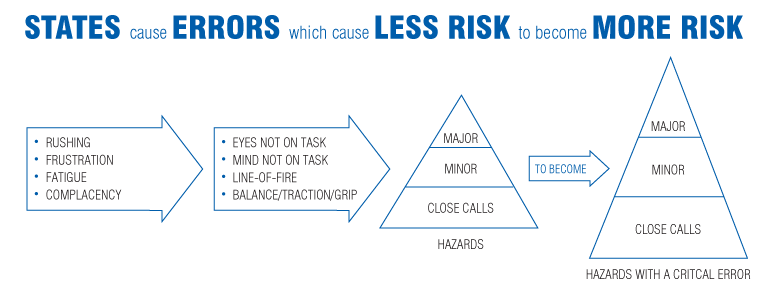

“In other words,” you say, “the four states: rushing, frustration, fatigue and complacency cause or contribute to four injury causing errors or mistakes: eyes not on task, mind not on task, moving into or being in the line-of-fire or somehow losing your balance, traction or grip.”

“What we can do is teach people that over 90% of all the injuries out there—at work, at home or on the highway—are caused by one or more of these four states causing or contributing to one or more of these errors. (You show him the risk patterns in Figure #1.) Since the state comes before the error, we can teach people to trigger on the state so they don’t make the error, and hence don’t increase the risk.”

He looks a bit lost, so you say “For example, you could realize as you’re rushing to the airport that looking at your watch every 30 seconds won’t get you there any faster. It will just take your eyes off the road.”

He nods. It looks like he’s getting it. He studies the risk pattern in from of him.

“I can see how you could trigger on the rushing or the frustration or the fatigue,” he says, “but how do you trigger on complacency?”

“Well,” you say, “you’re right. You can’t trigger on complacency but we can train everyone to observe other people for these state to error risk patterns. Every time they look for these patterns, they’ll automatically be thinking more about their own safety. We’ve also got to get them to work on improving their habits like moving their eyes before moving their body or car or forklift.”

“How exactly are we going to get them to do all of this?” he asks.

“Well that’s not all we’ve got to teach them,” you say. “We’ve also got to teach them to analyze all their close calls and small bumps and bangs in order to figure out whether it was a state they didn’t trigger on or a habit they still need to work on.”

“So,” he says, “as I said before, exactly how are we going to teach them all this?”

“It’s only four things,” you say, “trigger on the state, observe others, work on habits and analyze close calls. It’s not going to be all that hard to teach them these four techniques. The hard part is going to be motivating them enough to put some real effort into improving.”

“Why’s that?” he says.

“Because everybody thinks they’re safe enough already,” you say. “After all, how many people do you know who think they’re just an accident waiting to happen?”

He nods, “I see what you mean. Nobody thinks they have any problems, so why do anything – is that it?”

“Exactly!”

So he says, “How do we get everyone else on board? I mean,” he continues, “it makes sense and all. But if we don’t get it across in the right manner, they might just think we’re dumping it all on them.”

“Right again!” you say. “The key will be letting them figure it out for themselves, at least that’s how I think we should do it. Instead of just telling them what they need to know, maybe this time we should go at it a little differently.”

“I think you’re right,” he says. “Let me know when you’ve got it all put together and we’ll present it to the VP.”

The tone and the look back down at his paperwork signals the meeting is over, but you think to yourself, as you walk out… it’s a start.

Larry Wilson has been a behavior-based safety consultant for over 25 years. He has worked with over 2,500 companies in Canada, the United States, Mexico, South America, the Pacific Rim and Europe. He is also the author of SafeStart, an advanced safety awareness program currently being used by over 2,000,000 people in 50 countries worldwide.

No comments:

Post a Comment