How Will You Build Your Ideal Safety Culture?

In the past, organizations have focused on improving safety by addressing the work environment. Fixing hazards, providing better tools and equipment, and developing and enforcing adequate procedures are all approaches that, understandably, have worked well at improving safety. But many organizations have reached a plateau, finding that relying primarily on these approaches without taking a more comprehensive view of safety produces only marginal gains.

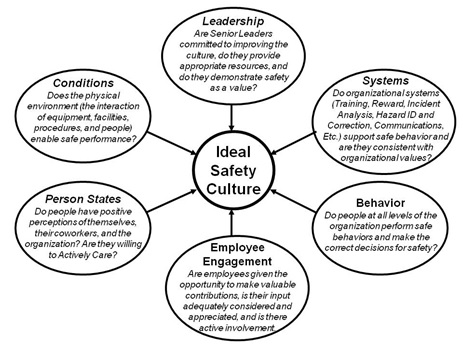

An ideal safety culture would develop continuous improvement activities around at least six components of safety depicted in Figure 1 below, including Leadership, Systems, Behaviors, Employee Engagement, Internal Person Factors, and Conditions.

Leadership

It’s the responsibility of leadership to foster an environment of safety. When leaders effectively communicate they truly don’t want unnecessary risks to be taken because they care about people not getting hurt and ensure systems are in place to adequately protect the workforce, it can motivate a more comprehensive safety culture as opposed to primarily focusing on reducing the injury rate numbers.

Although senior leaders are often held accountable for outcome numbers such as injury rate, they will be less effective if they simply, in turn, manage safety by using these same outcome numbers to motivate others. Because outcome numbers in occupational safety are typically based on the relatively rare occurrence of an injury, these numbers are too often reactive, reflect failure, and are not diagnostic for prevention.

The most effective leaders go beyond a focus on outcome numbers to hold people accountable for accomplishing proactive process activities and the development of system protections that contribute to eventual group and organizational success in productivity, quality, and safety.

Systems

Organizations rely on a number of safety management systems to manage risk and thereby decrease the chance of incidents and injuries. These systems generally include safety rules and procedures, safety training, hazard identification and correction, discipline, incident reporting and investigation, safety communications, safety suggestions, and rewards/recognition. Each safety management system has an important contribution to make in terms of not only improving workplace safety but also influencing an organization’s safety culture.

But we shouldn’t wait until an injury or other incident spotlights a defective system. Instead of waiting for incidents to occur and then assessing the systems that may have influenced the event in a reactive manner, organizations serious about changing their safety culture should critically analyze each system, ensuring each not only enables its primary function but also does so in a way that builds an ideal safety culture before incidents occur.

Behaviors

Some at-risk behaviors can be easily changed (e.g., by showing someone a new/clearly better procedure, providing someone new tools/equipment, pointing out a previously unrecognized hazard). Other at-risk behaviors can be very difficult to change because such change is fighting against our basic human nature. At-risk behavior is often more comfortable, more convenient, faster, or easier. We also have past and present reward structures, past learning and habits, and cultural and organizational influences that may promote at-risk behavior.

Therefore, before attempting to change an at-risk behavior to avoid a certain hazard, it should be acknowledged that other considerations should typically come first. That is, before attempting to change behavior to avoid a hazard, other interventions should typically be considered, such as eliminating the hazard (substitution of materials, automation), engineering controls (guarding, interlocks), or removing individuals from the hazard (not requiring people to be present while the hazard is present).

However, because it is not always feasible to eliminate all hazards, remove people from all risky environments, or provide engineering controls to create an acceptable risk level, even when workplaces have been “designed” to reduce hazards, incidents and injuries still occur. Complex systems require a great deal of human contribution to maintain productivity, quality, and safety. Human error is the inevitable by-product of our necessary involvement in complex systems. To eliminate human error would require us to eliminate the best source of creativity, flexibility, and problem-solving ability. People are not perfect and will occasionally make mistakes despite their best intentions and working in the best of surroundings.

Therefore, no matter how safely our workplaces are designed, how thoroughly we train our employees, or how harshly we enforce compliance, we will still occasionally perform at-risk behavior. This is not intended to indicate a blame of employees but to highlight the need to focus on understanding when and why at-risk behaviors occur. When behavior-based safety (BBS) is implemented correctly, although it will typically focus on behavior as a starting point, a proper analysis of the behavior will identify the full variety of contributing factors influencing that behavior and will logically lead to a variety of corrective actions based on the reasons they are occurring.

Employee Involvement and Ownership

Authoritarian directives may efficiently communicate action plans, but they may also stifle internal motivation or self-persuasion. Behaviors performed to comply with a prescribed standard, policy, or mandate are other-directed. Such behaviors are accomplished to satisfy someone else, and they are likely to cease when compliance cannot be monitored. This happens, for example, when an employee works alone or when the standard safety precautions always taken at work are not followed at home for similar or even riskier tasks.

When the development of an action plan involves the people expected to carry out that plan, ownership for both the process and the outcome is likely to develop. In other words, when leaders give a reasonable rationale for a desired outcome and then offer opportunities for others to customize methods for achieving that outcome, they facilitate internal or self-directed motivation.

Internal Person Factors

An ideal safety culture not only means eliminating or mitigating hazards and at-risk behavior but also ensuring the methods used to bring about that change leaves people feeling better about themselves, their coworkers, their situation, and the organization. This requires developing intervention strategies that include elements of choice and personal control, employee involvement and ownership, and focusing on allowing employees to work to achieve valuable outcomes for safety instead of creating situations where those involved are primarily motivated by avoiding negative consequences.

Also, the perception of risk is often different from actual hazards. Therefore, the hazards most likely to cause harm are not necessarily the ones that get noticed and corrected. Addressing the reasons people don’t accurately recognize hazards and why we don’t always act on the hazards we identify (e.g., become complacent) is also critical. Understanding that working in situations where certain conditions exist such as excessive time pressure, discomfort, conflicting goals, poor human-machine interfaces, adversarial relationships, and recognition and feedback disproportionately focused on production instead of safety should also be considered a hazardous situation requiring correction or proper control.

Physical Environment/Conditions

In an ideal safety culture, we consider how safety is supported or inhibited through the interaction of equipment, facilities, procedures, and people and create a work environment that minimizes, contains, or controls serious hazards. We also develop contingency plans to mitigate any negative consequences when at-risk behavior, human error, or systems failures inevitably occur.

With a proactive approach to the physical environment, new and improved rules/procedures, equipment fixes, and hazard controls are developed before injuries have a chance to occur. Participation in this proactive approach is often more difficult to motivate because the consequences of our preventive activities are rarely soon or certain. We may never know how many injuries are prevented by our proactive behaviors. However, such behavior is required to continuously move toward an injury-free culture.

Conclusion

Reducing injuries requires a comprehensive view of safety as an interaction of the physical environment/conditions, leadership, organizational systems, the behaviors of all people in the organization, employee engagement, and people (their knowledge, skills, and abilities, and also how people feel about what they are doing). Only by treating safety as multidimensional and ensuring the principles of an ideal safety culture are integrated into each dimension will we continue to see sustainable and continuous improvement in this critical area of organizational and human performance.

Steve Roberts, PhD, is co-founder and senior partner at Safety Performance Solutions, Inc., and his specific areas of expertise include the design, implementation, and evaluation of behavior and people-based safety processes, the assessment of organizational culture to guide safety interventions, increasing employee involvement in safety activities, organizational management systems design, organizational leadership development, and understanding and reducing human error in the workplace. Steve Roberts, PhD, is co-founder and senior partner at Safety Performance Solutions, Inc., and his specific areas of expertise include the design, implementation, and evaluation of behavior and people-based safety processes, the assessment of organizational culture to guide safety interventions, increasing employee involvement in safety activities, organizational management systems design, organizational leadership development, and understanding and reducing human error in the workplace. |

No comments:

Post a Comment