Tectonic Setting – Active continent-continent collision zone

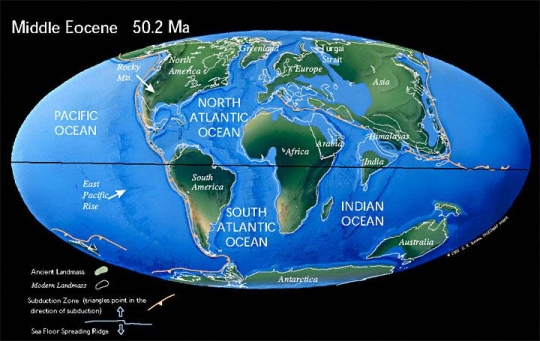

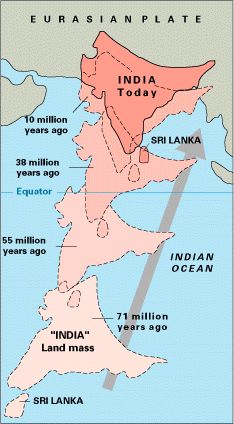

The Indian sub-continent is currently moving northward at about 40 mm/year and colliding with the Eurasian Plate (Tibetan Plateau). The collision with Asia began in the Middle Eocene era about 50-55 Myr ago (Figs. 1 & 2).

Fig. 1 – Distribution of continental land masses during the

Middle Eocene era (50.2 Ma before present) (Scotese, 1997)

Middle Eocene era (50.2 Ma before present) (Scotese, 1997)

Fig. 2 – Plate tectonic movement of India northwards

into the Eurasian Plate over the last 71 Myr (US Geological Survey)

into the Eurasian Plate over the last 71 Myr (US Geological Survey)

Global and Societal Significance

The region of north India is seismically very active. Major earthquakes pose a continuing threat to communities of that region. In addition, there is intra-plate earthquake activity south of the Himalayan Front that poses a threat to communities in other parts of the country, in particular in west India.- The 1934 magnitude 8.4 Bihar-Nepal earthquake killed about 10,700 people.

- The 1991 Camoli earthquake (not far north of Delhi) killed about 100 people

- In Peninsular India, a supposedly stable part of the sub-continent, the 1993 Mb 6.3 magnitude Killari earthquake killed about 7,500 people.

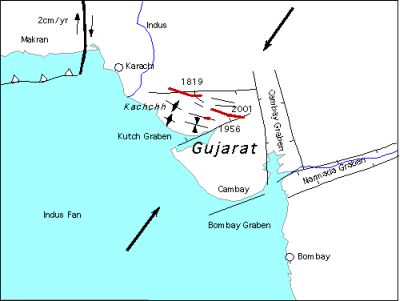

- The 2001 Bhuj earthquake (Mw 7.6) in western India killed over 19,000 people and injured about 166,000. About 340,000 houses were destroyed and an estimated 844,000 were damaged. The earthquake was in the same area as the 1819 Mw 7.7 earthquake.

- The 8 October 2005 magnitude 7.6 earthquake in the western Himalayan region in Pakistan killed about 79,000 people and injured more than 65,000. There were about 1300 killed in India and about 4300 injured.

Seismo-Tectonic Framework of India

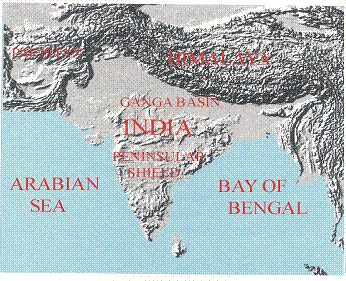

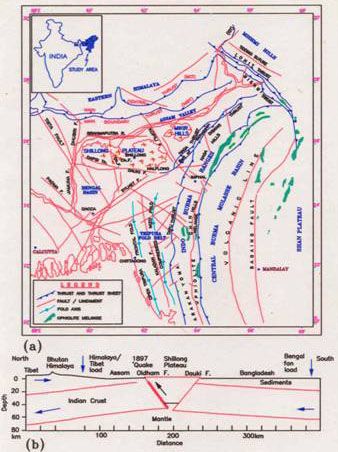

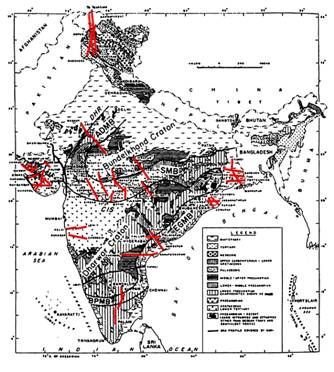

Peninsular India constitutes one of the largest Precambrian shield areas of the world (Fig. 3). The Indo-Gangetic Alluvium Plain (IGAP) separates the Himalaya to the north and the Peninsular Shield to the south (Figs. 3 & 4). The Shillong Plateau in northeast India constitutes an outpost separated from the main shield by the Bengal Basin and from the Himalaya by the Brahmputra River.

Fig. 3 – Topography of the Indian sub-continent, Tibet, Pakistan and Bangladesh

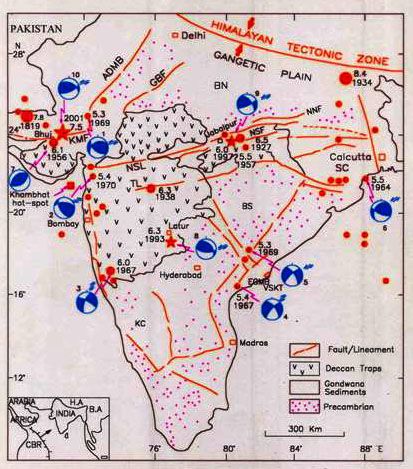

The Peninsular Shield of India is made up of three main cratonic regions (Fig. 4); the Aravalli, the Dharwar and the Singhbhum which are separated by Proterozoic rifts and mobile belts. The major prominent rifts that separate the southern and northern blocks of the shield are the Narmada Son Lineament (NSL) and the Tapti Lineament (TL), together called the Son-Narmada Tapti lineament (SONATA). The other rift basins are the Kutch, Cambay, Godavari, Cuddapah etc. (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4 – Seismo-tectonic map of India

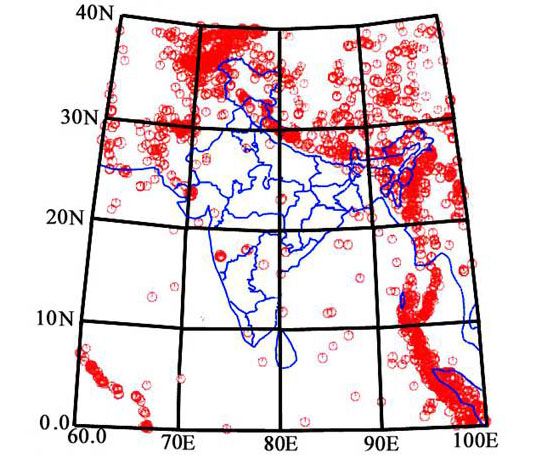

Fig. 5 – Seismicity of the Indian sub-continent, 1964-2002 (Magnitude > 5.0).

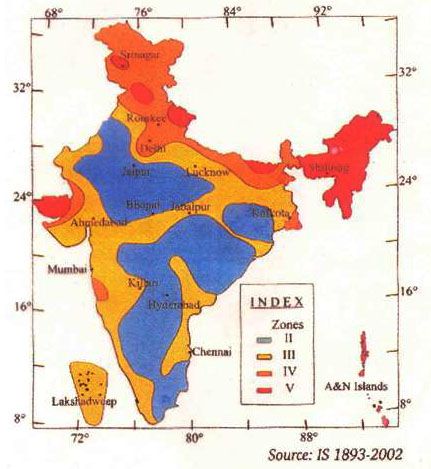

Fig. 6 – Seismic zonation within India.

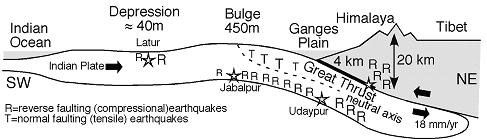

Fig 7 – Buckling of the Indian sub-continent as it collides with the Tibetan Plateau (Bilham, 2004)

Seismic Imaging in Northeast India

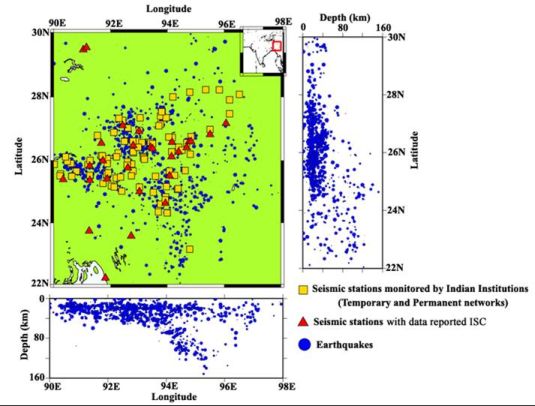

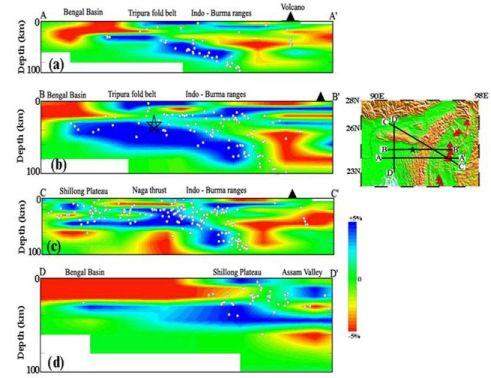

The northeast Himalayan region of India is one of the most seismically hazardous zones in the south Asia. GSI has determined the 3-D seismic velocity (Vp) structure of the crust of that region using selected arrival time data from two groups of shallow to intermediate-depth local earthquakes recorded by two different seismic networks (Fig. 8) by applying the 3-D tomography method of Zhao et al. (1992).

Fig. 8 – Seismicity and recording networks in northeast India.

One group of earthquakes consisted of 1011 shallow and intermediate-depth local earthquakes recorded during 1984-2000 by 113 temporary and permanent seismic stations in NE India (Figure 8). The other group of earthquakes consisted of 169 shallow to intermediate-depth earthquakes that occurred from 1964 to 2000 and were reported in International Seismological Center (ISC) Bulletins. These earthquakes were recorded by a network of 29 seismic stations (Fig. 8).

Fig. 9 – Lithospheric velocity profiles under northeast India.

red = low P-wave velocity regions. blue = high P-wave velocity regions.

white dots = earthquakes.

red = low P-wave velocity regions. blue = high P-wave velocity regions.

white dots = earthquakes.

The interpreted cross-sectional velocity images of the lithosphere in NE India (Fig. 9) demonstrate a good correspondence to the local and regional tectonic structures (Fig. 10) (Mishra et al., 2005a). The low-velocity zone down to 20 km depth in the region of the Bengal Basin corresponds to the thick sediments within the Bengal Basin, while high-velocity anomalies in the same depth range possibly indicate the presence of dense crystalline rocks under compressional stress that cause the seismicity in the region. The subducted Indian lithosphere is imaged as a high-velocity zone beneath the Burma platelet (Fig. 9).

Fig. 10 – Tectonic map of Northeast India.

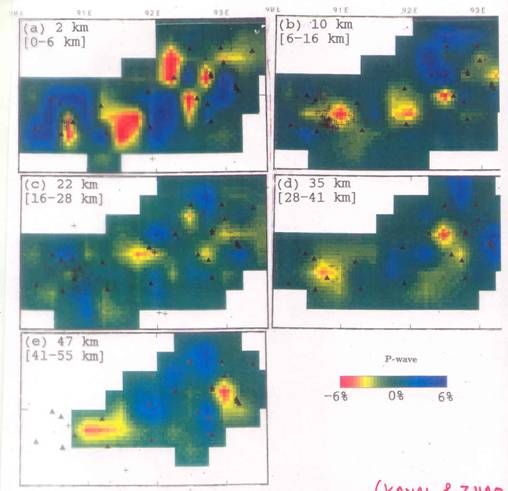

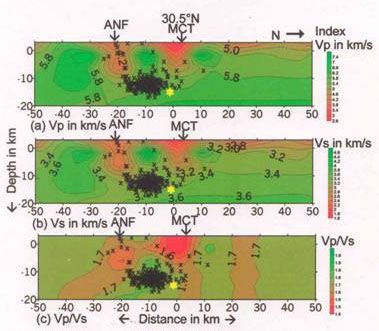

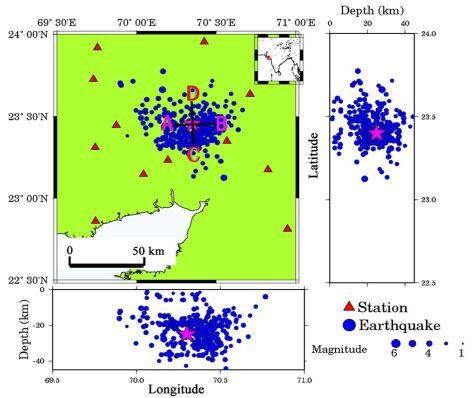

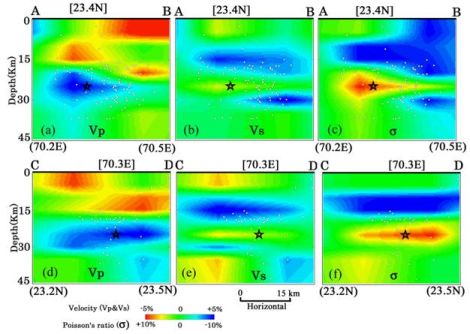

Kayal and Zhao (1998) imaged 3-D seismic velocities Vp and Vs, and the Poisson's ratio structures using microearthquake data recorded between 1983 and 1986 by a local seismic network (Fig. 11), which support the regional tomographic results of Mishra et al. (2005a) (Fig. 9).

Fig. 11 – P-wave velocity variations at 2 km, 10 km, 22 km, 35 km and 47 km depths

under northeast India (Kayal & Zhao, 1998)

under northeast India (Kayal & Zhao, 1998)

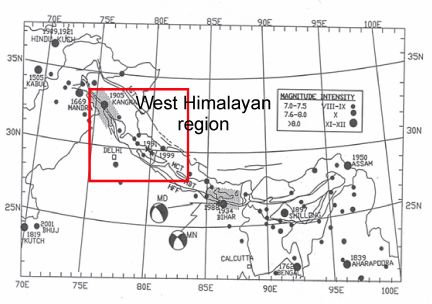

Aeismic Imaging of the Western Himalayan Region

Fig. 12 – Major earthquakes of the West Himalayan Region.

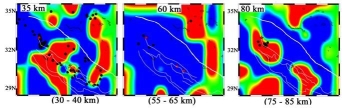

In the western Himalayan region, a detailed 3-D seismic image determined by Mukhopadhyay and Kayal (2003) beneath the 1999 Chamoli earthquake (M 6.3) epicenter area (Fig. 12) clearly shows that the major thrust zones; the mainshock and its aftershocks were in high-Vp zone of the "fault end" (Fig.13).

Fig. 13 – Seismic tomographic images (profiles) across the Chamoli area

of the western Himalayan region. MCT = Main Central Thrust.

of the western Himalayan region. MCT = Main Central Thrust.

Fig. 14 – Earthquakes and seismic recording networks used to determine

the P-wave velocity structure of the crust under the Chamoli region of the western Himalayan region.

the P-wave velocity structure of the crust under the Chamoli region of the western Himalayan region.

Fig. 15 – P-wave velocity variation "slices" at 5 km, 10 km, 15 km, 21 km, 35 km, 60 km and 80 km depth

under the western Himalayan region.

under the western Himalayan region.

Seismic Imaging of the Peninsular India Region

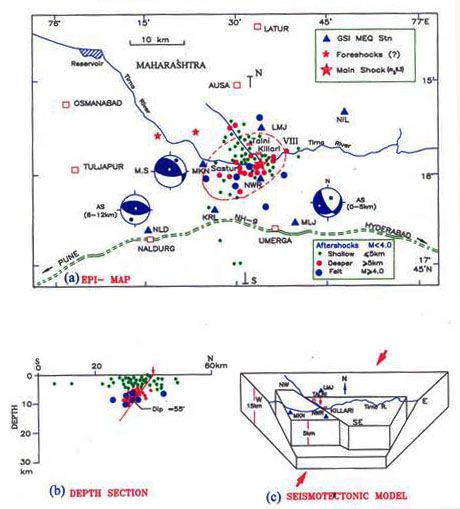

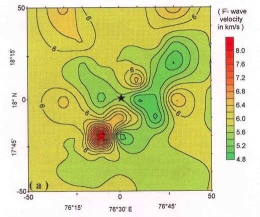

In Peninsular India, detailed seismic imaging has been done using P- and S-wave arrival times from the aftershock sequence of the 1993 Killari earthquake (M 6. 3) that occurred in the southern Archaean shield and using the sequence of the 2001 Bhuj earthquake (Mw 7.7) that occurred in the Kutch Rift Basin (Fig. 4).The 1993 Killari Earthquake region: 3-D imaging of the 1993 Killari earthquake source area in central Peninsular India (Fig. 3) was done using the local earthquake tomography method of Thurber (1983). The seismic images show that the mainshock occurred at the boundary between a high and a low-Vp zone (Kayal and Mukhopadhyay, 2002) and it supports their intersecting fault model shown in Figures16 and 17.

Fig. 16 – The 1993 Killari earthquake sequence in central Penisular India

and a seismotectonic model for the region.

and a seismotectonic model for the region.

Fig. 17 – P-wave seismic velocity variation "slices" in the region of the 1993 Killari earthquake.

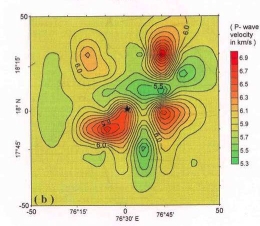

Fig. 18 – Aftershocks of the 2001 Bhuj earthquake in western India

and the seismic monitoring network used to determine images of the Earth's crust in the region.

and the seismic monitoring network used to determine images of the Earth's crust in the region.

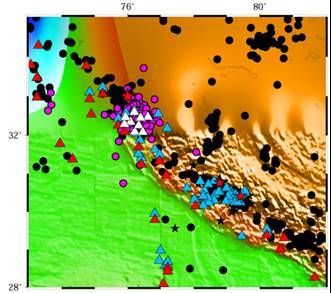

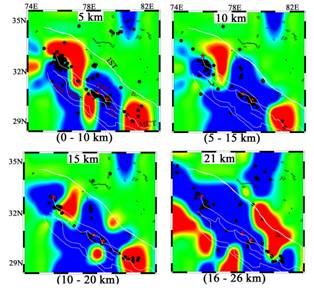

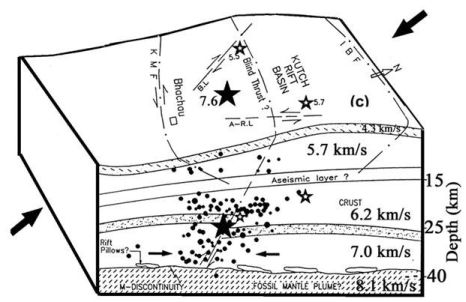

The 2001 Bhuj Earthquake region: Kayal et al. (2002), Mishra and Zhao (2003), Mishra et al. (2005b) estimated a detailed seismic structure using high precision P- and S-arrival times from a total of the 368 aftershocks (Fig. 18) using 3-D tomography method of Zhao et al. (1992).

Fig. 19 – Depth slices showing P-wave velocity variation

under the Bhuj earthquake regions. Red = low Vp velocities; blue = high Vp velocities.

under the Bhuj earthquake regions. Red = low Vp velocities; blue = high Vp velocities.

Fig. 20 – P-wave velocity, S-wave velocity and Poisson':s ratio profiles

across the region of the Bhuj earthquake (star).

across the region of the Bhuj earthquake (star).

The 3-D tomographic models are well correlated with a simulated model of the intersecting fault geometry derived from the fault plane solutions of the Bhuj earthquake sequence (Kayal et al., 2002b) (Fig. 21).

Fig. 21 – Tectonic model of the crust in the region of the Bhuj earthquake.

Fig. 22 – Bhuj earthquake damage, 2001

Fig. 23 – Simplified tectonic image of the Gujarat (Uni of Colorado)

Deep Seismic Sounding (DSS)

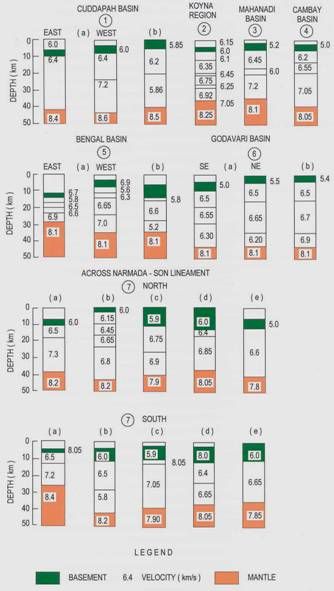

Deep seismic sounding (DSS) investigations have been made by the National Geophysical Research Institute (NGRI) group in many different parts of India (Fig. 24).

Fig. 24 – Location of deep seismic sounding (DSS) profiles throughout various regions of India

conducted by the National Geophysical Research Institute.

conducted by the National Geophysical Research Institute.

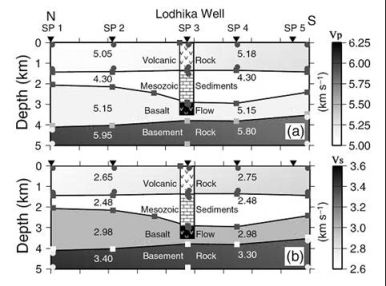

Fig. 25 – P-wave and S-wave seismic velocity profiles in the Lodhika Well area

showing sedimentary sequences beneath Deccan Traps.

showing sedimentary sequences beneath Deccan Traps.

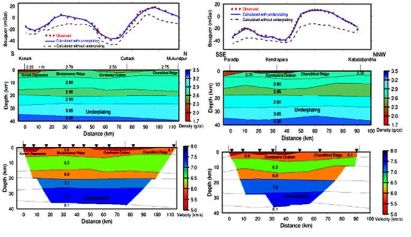

Fig. 26 – P-wave seismic velocity profiles across the SONATA zone

together with gravity modeling along the profiles.

together with gravity modeling along the profiles.

- Thickness of the Deccan traps varies from 100 m in the northeastern part to about 1500 m in the west coast,

- Hidden Mesozoic basins are delineated below the Deccan traps in the SONATA zone,

- Number of faults and their displacement pattern indicate block tectonics in the Peninsular India region,

- Crustal underplating is present in the SONATA zone. The presence of high velocity layers (7.0 – 7.3 km/s) from a depth of 8 – 12 km down to the Moho discontinuity is indicative of mafic ultramafic intrusives,

- The Moho discontinuity varies from 33 to 43 km in peninsular India region, below the SONATA zone Moho depth is deeper (40 - 43 km),

- Forward modeling of the refraction / reflection data yielded five layer velocity structure

- The seismic reflection data set identifies the presence of a suture at the Satpura mobile belt (Sain et al., 2002; Behera et al., 2004).

Fig. 27 – One-dimensional velocity/depth models from various regions of India.

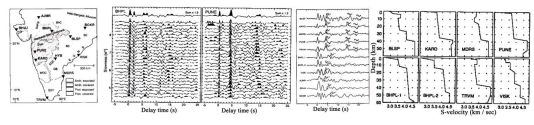

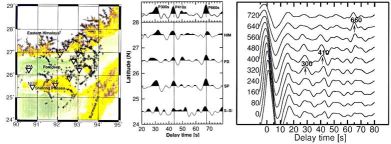

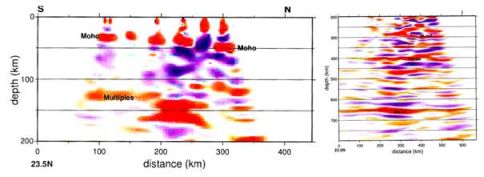

Seismic Receiver Function Studies

Seismic receiver function (RF) studies have been conducted out using teleseismic earthquake waves recorded at 10 broadband stations spread over Peninsular India (Fig. 28) and 5 stations over the northeast India regions (Fig. 29).

Fig. 28 – Results from RF studies across Peninsular India

showing S-wave velocity profiles of the crust.

showing S-wave velocity profiles of the crust.

A crustal thickness of 33-39 km is determined below the South India Archaean shield. The Deccan Trap basalts have not significantly affected the underlying crust. The predominant Proterozoic crust in the northern and eastern part of the shield, on the other hand, exhibits a complex character. The Moho conversions are considerably weaker compared to the Archaean terrains, and crustal thickness is 40 km and more (Kumar et al., 2001).

Fig. 29 – RF studies of the crust in Northeast India illustrating

the strong P-wave to S-wave energy conversion at the Moho.

the strong P-wave to S-wave energy conversion at the Moho.

In the northeast India region, thinner (33 km) Archaean crust is reported below the Shillong Plateau with the thickness increasing to ~40 km below the Brahmaputra valley and to ~50 km below the northeastern Himalaya to the north (Ramesh et al., 2005).

References

Behera et al., 2004, Journal of Geophysical Research, B12311, 1-25;Bilham, R., 2004. Earthquakes in India and the Himalaya: tectonics, geodesy and history. Annals of Geophysics, 47(2), 839-858;

Kayal and Zhao, 1998, Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 88, 667-676;

Kayal et al., 2002a, Geophysical Research Letters; 29, doi:10.1029/2002GL015177;

Kayal et al., 2002b, Journal of the Geological Society of India, 59, 395 – 417;

Kayal and Mukhopadhyay, 2002, Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 92, 2036 – 2039;

Kumar et al., 2001, Geophysical Research Letters, 28, 1397 – 1405;

Mishra and Zhao, 2003, Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 212, 393 – 405;

Mishra et al., 2005a, Journal of Geophysical Research (Revised the MS);

Mishra et al., 2005b, Geological Journal of India (Revised the MS),

Mishra et al., 2005c, Geological Society of India, Special Publication, 85, 337;

Mukhopadhyay and Kayal, 2003, Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 93, 1854 -1861;

Ramesh et al., 2005, Geophysical Research Letters, (in press);

Sain et al., 2002, Geological Journal of India, 150, 820 – 826;

Scotese, C. R., 1997. Palaeogeographic Atlas, PALEOMAP Progress Report 90-0497, Department of Geology, University of Texas at Arlington, Texas, 37 pp.

Thurber, 1983, Journal of Geophysical Research, 88, 826 – 836;

Zhao et al., 1992, Journal of Geophysical Research, 97, 19909 – 19928.

Contact

J. R. Kayal,CGD, Geological Survey of India

Kolkata, India

jr_kayal@hotmail.com

No comments:

Post a Comment