Gandhi And Deep Ecology

By Thomas Weber

The central importance of Gandhi to

nonviolent activism is widely acknowledged. There are also other

significant peace-related bodies of knowledge that have gained such

popularity in the West in the relatively recent past that they have

changed the directions of thought and have been important in encouraging

social movements - yet they have not been analysed in terms of

antecedents, especially Gandhian ones. The new environmentalism in the

form of deep ecology, very closely mirror Gandhi's philosophy. This

article analyses the Mahatma's contribution to the intellectual

development of Arne Naess and argues that those who want to make an

informed study of deep ecology and particularly those who are interested

in the philosophy of Naess, should go back to Gandhi for a fuller

picture.

Gandhi as a Source of Influence

Gandhi has had a profound and celebrated

influence on the nonviolence movement through Martin Luther King Jr,

Cesar Chavez, Helder Camara, Thomas Merton, Danilo Dolci, Gene Sharp and

many others. In this article, I examine Gandhi's influence on three

significant bodies of knowledge that have recently gained wide

popularity in the West and which have also stimulated important social

movements: deep ecology, peace research and what has become known as

'Buddhist economics', and particularly on the intellectual development

of leading figures in these fields: Arne Naess, Johan Galtung and E. F.

Schumacher.

Many environmental activists who claim that 'deep

ecology' is their guiding philosophy have barely heard the name of Arne

Naess, who coined the term. While Naess readily admits his debt to

Gandhi, works about him tend to gloss over this connection or ignore it.

For example, while a recent article on Naess' environmental philosophy

and the Gita (Jacobsen, 1996: 228-230) refers to the link, the chapter

on deep ecology in Merchant's book (1992: 88) which surveys 'radical

ecology' contains a long list of its sources, including the debt owed to

interpreters of Eastern philosophy such as Alan Watts, Daisetz Suzuki

and Gary Snyder, without even mentioning Gandhi. The deep ecology of

Naess not only talks of a personal identification with nature, but also

of self-realization being dependent upon it. For those who know Gandhian

philosophy well, this line of reasoning is readily recognized. However,

Naess' writings on Gandhi are not particularly well known and Gandhi's

influence on him has not received due recognition.

Peace research is a diverse field and Gandhi's influence

has only touched certain areas of it. While he is generally not

mentioned, and potential causal links are rarely investigated, the

literature on conflict resolution is commonly quite 'Gandhian' in its

approach. In much of the international relations, defence, security,

ethnic conflict and related peace areas the possible relevance of

Gandhian philosophy is not even an issue considered worthy of

investigating. Although the connection between the two receives scant

attention or is very much implicit (see Sorensen, 1992: 143-144, note

15), and a recent speech has called for the 'adding of Gandhi to

Galtung' (Herman, 1994), the work of Johan Galtung, one of the leading

academics in the peace research area, is centrally and obviously

influenced by Gandhian philosophy· While Galtung makes several

references to this influence on his thought in the introductory chapters

to his Essays in Peace Research and elsewhere (e.g. Gage, 1995: 7),

even Lawler (1995), the recent chronicler of Galtung's peace research,

does little more than mention it in passing. For him Galtung seems to

have moved from positivism to Buddhism, while according to Galtung

himself it was Gandhi all the time'.

Unlike the works of Naess and Galtung,

Schumacher's writings have made it onto popular bestseller lists· The

Gandhian connection, at least at a superficial level, was originally

also more explicit· However, Schumacher's 'small is beautiful'

philosophy eventually came to be known as 'Buddhist economics and

gradually the links with Gandhi took a back seat. His concern for

Third-World poverty led to the formation of the Technology Group to

develop tools and work methods which are appropriate to the people using

them. While this practical work can only be lauded, its philosophical

under-pinning should also be remembered.

Arne Naess and Deep Ecology

Although a conservation ethic had been

around for decades (Nash, 1989) before the publication of books such as

Carson's Silent Spring (1962) and studies such as The Limits to Growth

(Meadows et al., 1972), Arne Naess took environmental philosophy into

new areas with his call for a 'deep ecology'.

In 1973, Naess provided a summary of a

lecture given the year before in Bucharest at the World Future Research

Conference. That short article (Naess, 1973) was to take on

paradigm-shifting proportions. It introduced us to a terminology that

has since become commonplace.

Naess (1973: 95) points out that a shallow

but influential ecological movement and a deep but less influential one

compete for our attention· He characterizes the 'shallow' ecological

movement as one that fights pollution and resource depletion in order to

preserve human health and affluence, while the 'deep' ecological

movement operates out of a deep-seated respect and even veneration for

ways and forms of life, and accords them an 'equal right to live and

blossom'.

In a later elaboration, Naess puts the

contrast between the two in its most stark form: shallow ecology sees

that 'natural diversity is valuable as a resource for us'. He notes that

'it is nonsense to talk about value except as value for mankind', and

adds that in this formulation 'plant species should be saved because of

their value as genetic reserves for human agriculture and medicine'. On

the other hand, deep ecology sees that 'natural diversity has its own

(intrinsic) value' and he notes that 'equating value with value for

humans reveals a racial prejudice', and adds that 'plant species should

be saved because of their intrinsic value' (Naess, 1984: 257).

During a camping trip in California, Arne

Naess and George Sessions (1985: 69-70) jointly formulated a set of

basic principles which they presented as a minimum description of the

general features of the deep ecology movement: the 'well being and

flourishing' of human and non-human life have intrinsic value; the

richness and diversity of life forms contribute to the realization of

these values and are therefore also intrinsic values; humans have no

right to reduce this richness or diversity except where it is necessary

to satisfy vital needs; the flourishing of human life and culture is

compatible with a large decrease in the human population, and a

flourishing of non-human life requires it; human interference with

nature is excessive and increasing; and, therefore, economic,

technological and ideological policies must change. This ideological

change will mean an appreciation of the quality of life rather than the

standard of living; and those who subscribe to these points 'have an

obligation directly or indirectly to try to implement the necessary

changes'.

Naess loved nature and identified with it

from early childhood. As a philosopher he researched and was influenced

by Spinoza (Rothenberg, 1993: 91-101) who maintained a spiritual vision

of the unity and sacredness of nature and believed that the highest

level of knowledge was an intuitive and mystical kind of knowing where

subject/object distinctions disappeared as the mind united with the

whole of nature. However, as important as those inputs were, the

influence of Gandhi is also clearly visible in his formulation of deep

ecology. In fact Naess himself admits in a brief third-person account of

his philosophy that 'his work on the philosophy of ecology, or

ecosophy, developed out of his work on Spinoza and Gandhi and his

relationship with the mountains of Norway' (Devall & Sessions, 1985:

225).

Gandhi experimented with and wrote a great

deal about simple living in harmony with the environment (Power, 1991)

but he lived before the advent of the articulation of the deep

ecological strands of environmental philosophy. His ideas about human

connectedness with nature, therefore, rather than being explicit, must

be inferred from an overall reading of the Mahatma's writings. Naess

(1986:11) explains that 'Gandhi made manifest the internal relation

between self-realisation, non-violence and what sometimes has been

called biospherical egalitarianism', and points out that he was

'inevitably' influenced by the Mahatma's metaphysics 'which contributed

to keeping him (the Mahatma) going until his death'. Moreover, 'Gandhi's

utopia is one of the few that shows ecological balance, and today his

rejection of the Western World's material abundance and waste is

accepted by progressives of the ecological movement' (Naess, 1974: 10).

While Gandhi allowed injured animals to be

killed humanely to save them from unreasonable pain and at times even

because they caused undue nuisance, his nonviolence encompassed a

reverence for all life. In his hut at the Sevagram Ashram there is a

large pair of wooden tongs which were used to pick up snakes so that

they could be taken beyond the perimeter and released as an alternative

to killing them.

A review of the Gandhian literature (while

keeping in mind the time in which it was written as a reason for

anthropocentric expression) readily reveals statements such as: 'If our

sense of right and wrong had not become blunt, we would recognise that

animals had rights, no less than men' (Hingorani, 1985: 10); 'I do

believe that all God's creatures have the right to live as much as we

have' (Harijan, 19 January 1937); and 'We should feel a more living bond

between ourselves and the rest of the animate world' (Patel &

Sykes, 1987: 50). The clearest indication of Gandhi's respect for

nature, however, comes through his interpretation of the Hindu worship

of the cow. Gandhi saw cow protection as one of the most wonderful

phenomena in human evolution. 'It takes the human being beyond his

species. The cow to me means the entire sub-human world. Man, through

the cow, is enjoined to realise his identity with all that lives' (Young

lndia, 6 October 1921).

Another way to illustrate Gandhi's

concerns with the oneness of life is to look at his writings on ahimsa.

Usually translated as

nonviolence, it can be seen as the fountainhead of Truth - the ultimate

goal of life. From his prison cell in 1930, Gandhi wrote to his

ashramites that 'Ahimsa and Truth are so intertwined that it is

practically impossible to distangle and separate them. They are like two

sides of a coin ...' (Gandhi, 1932: 6).

For Gandhi, ahimsa meant 'love' in the

Pauline sense and was violated by 'holding on to what the world needs'

(Gandhi, 1932: 5). As a Hindu, Gandhi had a strong sense of the unity of

all life. For him, nonviolence meant not only the non-injury of human

life, but as noted above, of all living things. This was important

because it was the way to Truth (with a capital 'T') which he saw as

Absolute - as God or an impersonal all-pervading reality - rather than

truth (with a lower case 't') which was relative, the current position

on the way to Truth.

Naess had been an admirer of Gandhi since

1930 (Naess, 1986: 9). When he read Romain Rolland's Gandhi biography

(Rolland, 1924) as a young philosophy student in Paris in 1931, he must

often have come across Gandhi's statements on Truth and the essential

oneness of all life. In some of his works, Naess notes that 'nature

conservation is non-violent at its very core' and quotes Gandhi to this

effect:

I believe in advaita (non-duality), I

believe in the essential unity of man and, for that matter, of all that

lives. Therefore I believe that if one man gains spiritually, the whole

world gains with him and, if one man fails, the whole world fails to

that extent. (Young India, 4 December 1924)

As this implies, for Arne Naess deep

ecology is not fundamentally about the value of nature per se, it is

about who we are in the larger scheme of things. He notes the

identification of the 'self' with 'Self' in terms that it is used in the

Bhagavad Gita (that is, as the unity which is one) as the source of

deep ecological attitudes. In other words, he links the tenets of his

approach to ecology with what may be termed self-realization. And here

the influence of the Mahatma is most clearly discernible. Naess notes

(1986: 9) that while Gandhi may have been concerned about the political

liberation of his homeland, 'the liberation of the individual human

being was his supreme aim'.

The link between self-realization and

Naess' environmental philosophy can be clearly seen in his discussion of

the connection between nonviolence and self-realization in his analysis

of the context of Gandhian political ethics. Starting with the 'one

basic proposition of a normative kind' when investigating Gandhi's

teachings on group conflict - 'Seek complete self-realisation' (the

manifestation of one's potential to the greatest possible degree') -

Naess summarizes this connection as:

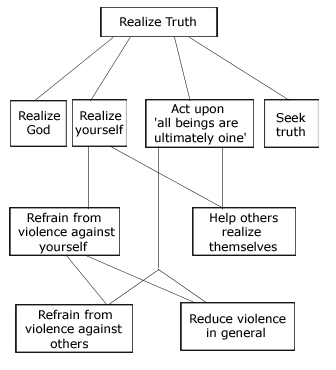

Figure 1. Naess' Systematization of Gandhian Ethics

- Self-realization presupposes a search for truth.

- In the last analysis, all living beings are one.

- Himsa (violence) against oneself makes complete self-realization impossible.

- Himsa against a living being is himsa against oneself.

- Himsa against a living being makes complete self-realization impossible.

(adapted from Naess, 1965: 28-33)

This conceptual construction evolved into

ever more complex and graphic presentations. In his 1974 work, Naess

provides various systematizations of Gandhi's teachings on group

struggle where self-realization is the top norm and which contain the

critical hypothesis that all living beings are ultimately one, as set

out in in Figure 1.

In a discussion with David Rothenburg over

human destruction of the environment without adequate reason (for

example, where a parent kills the last animal of a species to save his

or her child from its attack), Naess is asked whether protection of

nature should occur because we should think not only of ourselves or

because natural things are part of us also. Naess refuses to separate

the two approaches. He answers with another allusion to Gandhi: 'When he

was asked, "How do you do these altruistic things all year long?" he

said, "I am not doing something altruistic at all. I am trying to

improve in Self-realisation"' (Rothenberg, 1993: 141-142). There need be

no divide between the intrinsically valuable and the useful. And, in a

Gandhian way of feeling rather than intellectualizing, he adds: 'if you

hear a phrase like, "All life is fundamentally one", you should be open

to tasting this, before asking immediately, "What does this mean?"'

(Rothenburg, 1993:151).

Along with other deep ecological

theorists, Naess is attempting to clarify what the deep ecology movement

stands for. Ecological philosophies are continually expanding, and

other writers have also added their analytical skills to the deep

ecology literature (see, for example, Devall & Sessions, 1985).

Recently, we have seen the rise of eco-feminism, Lovelock's Gaia

hypothesis and aggressively radical movements and philosophies such as

Earth First! While Gandhi certainly would not have welcomed some of

these later developments (for example, the employment of 'ecotage'

techniques such as tree-spiking and the disabling of logging equipment),

and Naess does not, the Mahatma's influence is clearly discernible

through the writings of Arne Naess.

No comments:

Post a Comment